December 17, 2015: Glancing sideways

It's a hard concept to grasp for some. The idea that to find European ancestors we have to find out about them in the U.S. seems counterintuitive. But it's exactly the right procedure to follow.

Without a city or district of origin, you'll never close in on the archive or repository that holds records pertaining to them in the old country. You need a starting place. And it's very likely that a clue to their home base is buried in the American town where their families settled.

There's a value, too, in looking for siblings of the person you hope to track down. The sideways step can lead to productive information

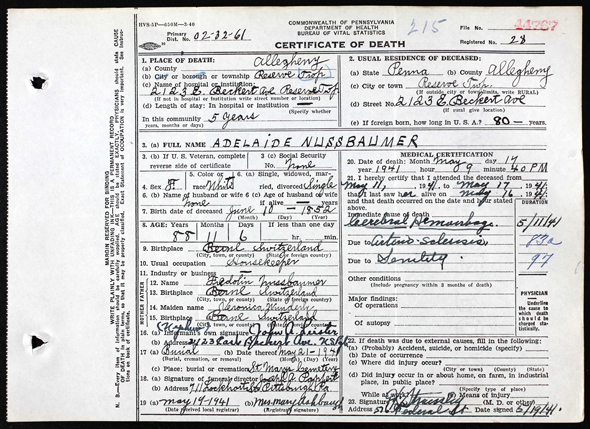

Adelaide Nussbaumer isn't part of my family, but she was the sister of a person trying to track down this family's original home in Switzerland. We're fortunate that Pennsylvania is now sharing images of some of their death records, such as this collection called "Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963" at Ancestrylibrary.com. The person was searching for information about the parents of Adelaide, Fridolin Nussbaumer and Verena Wenderle. She had the name of her direct ancestor but not the sisters and brothers.

Adelaide's 1941 death certificate gave her birthplace as Berne, Switzerland. Bern or Berne is a Bundesstadt or "federal city" and it's where a number of Swiss civil registrations were recorded from 1792-1876. A number of Nussbaumers appear in the Familysearch.org online index "Switzerland, Bern, Civil Registration, 1792-1876." Perhaps something will turn up there for Fridolin and Verena.

At the very least, it's certainly a clue to the new direction!

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

Write A Comment

December 4, 2015: Look it up

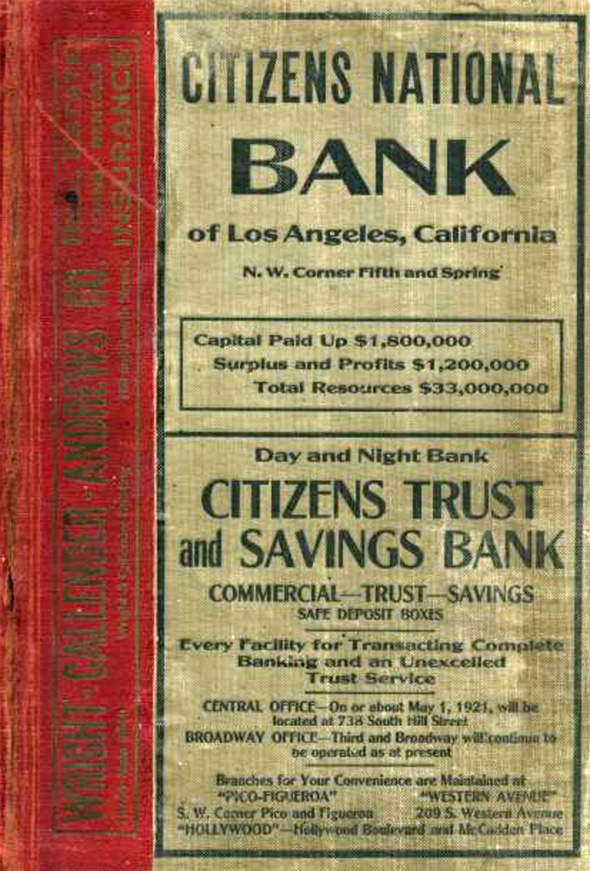

This impressive collection of Los Angeles (and vicinity) city directories is housed online as part of the Los Angeles Central Library collection. When your elusive ancestor lived in L.A. only between 1920 and 1930, this collection can be a goldmine of possibilities. Not only is Los Angeles represented from 1875-1987 in this discontinuous collection, but there are scattered directories for Santa Monica, Watts, Westwood, and other communities.

The city was much smaller then, but the need to find housing outstripped the city's ability to provide it. So homeowners became landlords and rented out converted garages or rear structures for a monthly income. When someone's address is marked as, say, "1120 1/2 (r) E 22d" you know you're not dealing with a homeowner, and that it would be fruitless to search for property records.

David Stein is one such elusive fellow. He doesn't appear in the 1920 or 1930 census at any address we have for him. We don't know his age. We know he had a wife called Anne from a deed of sale, and we know that when the deed was processed he and Anne lived in the rear apartment at 1120 East 22nd Street in Los Angeles, a neighborhood then (as now) just a tad southeast from downtown proper.

In fact there are a good handful of David Steins from 1920 to 1930 living in roughly the same neighborhood, which was close to east-side Boyle Heights, then the center of the Jewish neighborhood. The illustrious Canter's Deli was there at the time and so were other Jewish shopping areas and synagogues.

One of the David Stein candidates, the one at 1366 East 21st Street, was a rabbi, a fact not revealed in this 1926 directory entry just above, but we know it from his declaration of intent to become a U.S. citizen. The same address was listed on his papers.

The David Stein at 1786 West 37th was a chauffeur, but he's not at the address we're looking for, so we can eliminate him as a likely suspect.

From the 1926 directory entry we know that our David on 22nd Street was a salesman, but what he sold wasn't revealed.

The sum total we know about our David: he rented a home at the address above, he was a salesman, he had a wife called Anne. But where he went after this brief appearance in Los Angeles is anyone's guess...and leaves a frustratingly fragmentary trail for us to puzzle over and -- someday, we hope -- to solve.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

November 18, 2015: The lady in question

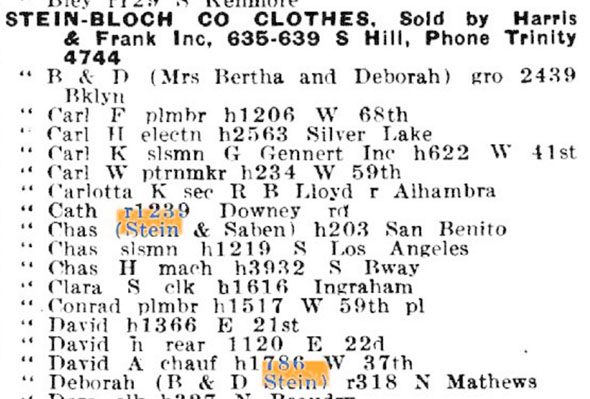

Who she is is anyone's guess, and guessing is our only option here.

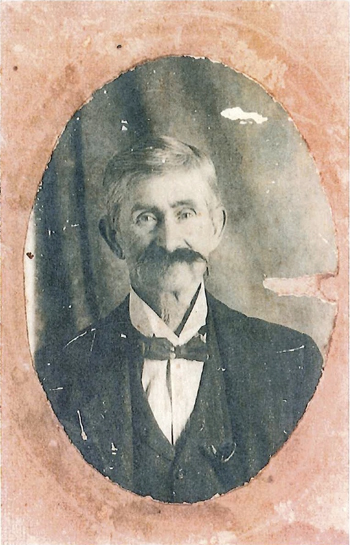

We know she was in Charleston, South Carolina, likely not born there but a resident at some point. The family who ended up with this daguerreotype was that of Carl Louis Henry Müller, who was regularly known as Louis Müller. His wife, Mary Amme, had a mother born in Germany and living in Charleston, but Catherine Klesieck was born in 1826 and was too young to be this woman, who appears to have prepared herself for this portrait in the 1850s.

There's a better candidate, in fact. Louis Müller's grandmother was born in 1785 as Jacobina Elisabetha Lommel in Frankfurt am Main. Sometime after her son Ludwig Müller became pastor at St. Matthew's German Lutheran Church in 1848, Mrs. Müller made the long voyage to Charleston to join her son.

Jacobina (or Jacoba, as her name is rendered in her 1858 St. Matthew's death notice) lived until her grandson Louis was ten years old. Whoever received her photo was probably the luck of the draw, but nevertheless it was part of the collection that Louis' descendants currently own...unmarked and undated, of course!

But there are some resemblances between the older Pastor Ludwig Müller and his presumed mother. The noses in particular, both strong and resolute, are noteworthy. So are the blue eyes in both. See this image for an enlargement of Ludwig's face, where his light blue eyes are obvious even in black-and-white.

The older lady is wearing a simple dark dress with high ruffled collar and cloth-covered buttons typical of the late 1850s, plus an oval cameo or neck ornament. Her hair is pulled back simply behind her head. Younger women might have had elaborate curls in the 1850s but older ladies were more likely to keep it simple.

Looking through other available images from this family, no other candidate seems to fit the age and timeframe suggested by the use of this daguerreotype process or the type of sartorial and tonsorial choices made.

Ludwig Müller's own wife Caroline Laurent Müller was decidedly too young (and too formidable!) to be a candidate for this demure and stately image. Nor do any of the other women associated with the Müller clan and their in-laws in Charleston during this era suggest themselves as candidates.

So while we can't confirm the identity of our Müller-related lady, the likelihood that this is a treasured keepsake and someone important to the family leads us to explore this theory. If it's really Jacobina, we do have a treasure indeed.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

November 1, 2015: Just out of reach

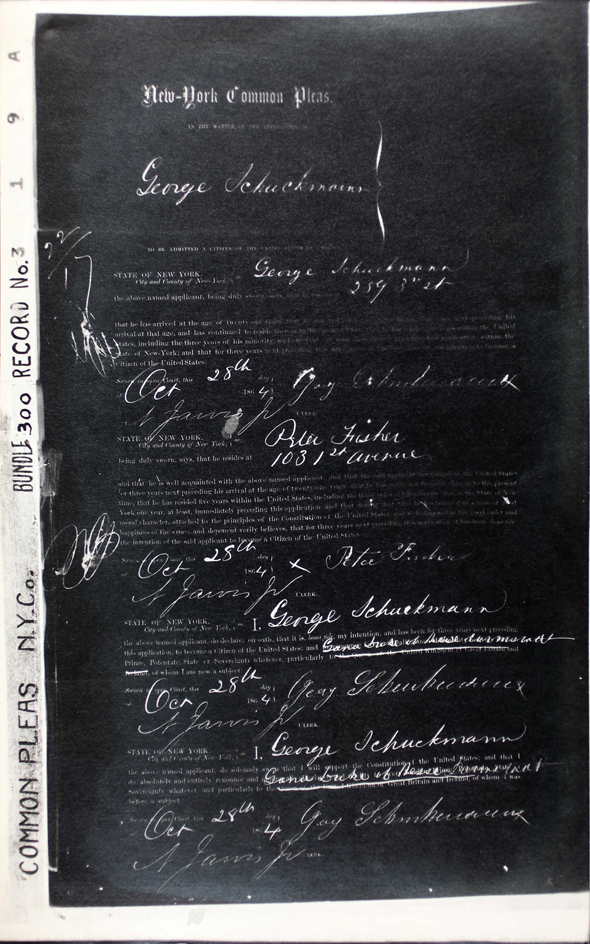

Here's an old record from New York in desperate need of re-filming. Click on the image to enlarge.

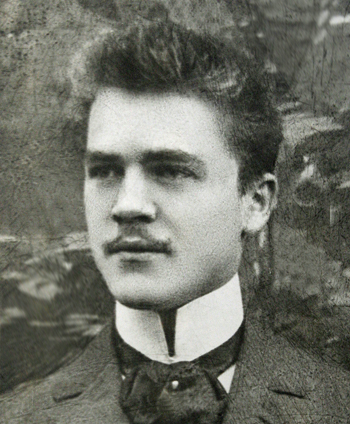

This fellow could very well be related to our Charleston, South Carolina Schuchmanns (whose name was regularized to Schuckmann) although he first ended up in Brooklyn, New York and then in Savannah, Georgia.

George Philip Schuchmann kept the original German spelling of his surname. From the New York City Book of Common Pleas, this fellow is at this date twenty one years old and ready to become a citizen, having renounced what looks like (or is meant to be) the Grand Duke of Hesse Darmstadt.

Some of the text remains just beyond legibility and focus. Here's a positive image of the same document but it's not much easier to read.

We know our George Schuchmann was indeed from Hesse Darmstadt but there's some uncertainty how old he really was in 1864. A ship manifest for the ship Madison listed him (or someone with an identical name) as 19 years, six months. But once George decamped to Savannah his age consistently points to a birth year of 1848 or 1849.

This is an ongoing project to be solved at some point in the future...not very far in the future, we hope.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

October 10, 2015: William Müller of Atlanta and Charleston

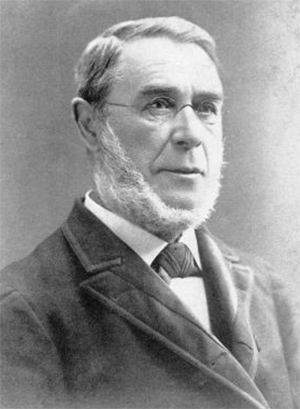

This headstone at Fulton Cemetery in Atlanta marks the resting place of Matthias Friedrich Wilhelm Müller, who had long since Anglicized his name to William Müller.

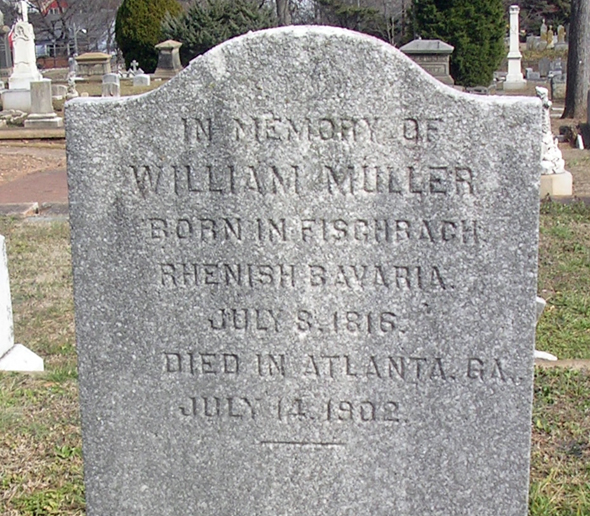

Although William's younger brother Ludwig (Louis) Müller D.D. remained in South Carolina, Pastor Müller still kept his older brother's name in mind for his six child, duly named William Albert Christian, born in 1857 in Charleston. Ludwig named his first son for yet another brother, Frederick, who never emigrated to America as far as we know.

Like his father, William (known as W.A.C.) was also a Lutheran pastor and spent some time back in Germany to study as his father did. After a stint at a congregation in Pennsylvania, W.A.C. came back to Charleston to support his father's parish and was happily preaching into the 20th century.

Did William the younger ever meet William the older? Entirely likely, and probably at his baptism at St. Matthew's parish.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

September 16, 2015: Treasures from the past

Both Ancestry.com and Ancestrylibrary.com have released a new series of online databases for digital wills and probate information.

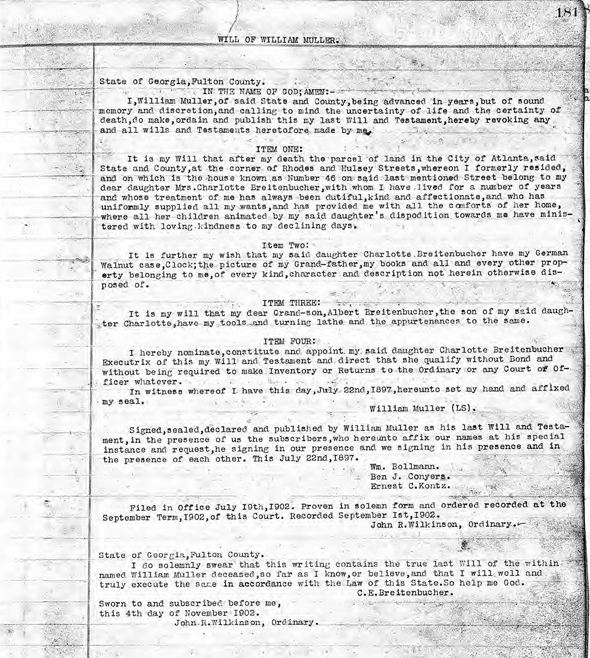

Nothing obvious came up from searches on my common ancestral surnames in South Carolina and Illinois, but once I searched for a surname without specifying the state, I got an unexpected hit from "Georgia, Wills and Probate Records, 1742-1992": a link to the will of William Müller of Atlanta, Georgia, brother of my great-great-grandfather Rev. Ludwig Müller of Charleston.

Gradually I'm getting to know more about William and his descendants. He was born Mattias Friedrich Wilhelm Müller on July 8, 1816 in Hochspeyer, Rhineland-Pfalz, and he emigrated with his wife Louisa Poch and their children, probably in the early 1850s. He spent at least some time in Pickens, South Carolina as a carpenter before settling in Atlanta as a master mechanic.

He lived a long and happy life, eventually residing with his daughter Elisabeth Charlotte Breitenbucher, as indicated in the will above (click it to enlarge and read more comfortably). The website Find A Grave includes a transcript of the 1902 obituary printed in the Atlanta Constitution.

What intrigues me about the will is Item Two, wherein William listed the items he wanted his daughter to inherit: a German walnut case of some kind, a clock, and "the picture of my Grand-father" in addition to books and other belongings.

By picture, William can't mean a photograph. He must be referring to a painting, and with only two grandfathers, this can only mean either his paternal grandfather Johann Michael Müller, who lived about 1730-1805, or his maternal one, Johan Georg Lommel, whose birthdate we don't know but who died in 1809.

The possibility of finding this portrait, either still with descendants of William, or perhaps in an Atlanta museum somewhere, is an alluring thought. But it could easily have drifted away from the family collection, as some tenuous items do over time.

It's worth exploring, however, and I've reached out to cousins from William's line to see what they may know.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

September 2, 2015: Handy with a needle

You never know what will happen when you take your basic search engine and plug in your ancestor's name.

In this case, using the name Elise Schuckmann Jatho and Chalreston, the city where she lived after emigration, up popped this gem.

The Charleston Museum has been collecting artwork produced its citizens for centuries, and my great-grandmother's hand-worked embroidery is now a part of the local collection. It's too delicate for public display, but this is almost better: an entire museum at the click of a mouse!

Billed as America's first museum, it was founded in 1773 with a focus on the South Carolina Lowcountry, of which Charleston was certainly a part.

Elise's mother was the better known seamstress. Marie Dressel Schuckmann was the focus of several newspaper stories highlighting her flag-making skills, but the fact that her daughter was so accomplished at a young age really shouldn't be a surprise, considering her mother's talent.

Elise's rendering the the flowers is particularly delicate, with most of the blossoms identifiable. I certainly see morning glories, violas, chrysanthemums, and periwinkle, among others.

I contacted the museum to ask how they were sure about the identity and date of this bit of embroidery, and they had records of the actual donation of the piece. One of Elise Shuckmann Jatho's granddaughters, Maryliese Jatho, inherited the embroidery from her grandmother Elise. It was Elise herself who told her she'd embroidered the piece when she was fourteen years old.

That's a helpful bit of information. Elise was, in fact, fourteen in 1843. It also suggests, based on the plant forms pictured here, that she was copying southern flowers, rather than having worked the piece in Reinheim, Hesse Darmstadt, where she was born and raised. The morning glories are helpful here, being a typical southern flower and not hardy in colder climates.

If you'd like to find out more about the Charleston Museum, visit their website.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

August 20, 2015: A doctor in the house

Medical folks are few and far between in our family history. In fact, we have only two. One is a current-day descendant of this man's father and is a practicing physician on the West Coast.

The other is this man: Dr. Charles Müller of South Carolina, a pharmacist and farmer.

He was born Johann Georg Carl Müller in Charleston, South Caroline. His parents were prominent in town. Charles' father was the Rev. Ludwig Müller D.D., pastor at St. Matthew's German Lutheran Church from 1848-1898.

Charles' mother, the former Caroline Laurent, was formidable in personality with an invented French pedigree designed to lure away researchers from her more accurate but decidedly humble birth.

Charles was educated in Charleston and married Margaret Cobb, the daughter of Ephraim Cobb and Louisa Turner. They seem to have had a yen for the country life and spent most of it in Wagener Township, Oconee County, very near the town of Walhalla, where Charles' father Ludwig had co-founded Saint Johns Evangelical Lutheran Church.

In fact, Reverend Müller spent so much time in Walhalla that the officials of St. Matthew's Church back in Charleston suggested that the good Reverend might want to choose which church he actually preferred! Rev. Müller wisely chose St. Matthews, but he, his family, and Charles' siblings kept in regular contact with their son/brother in Walhalla and Wagener over the years.

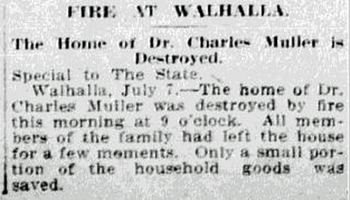

Charles and Maggie Müller raised eight children and had homes in both Wagener and Walhalla. Sadly they lost all their belongings in a house fire, as was reported in the newspaper The State on July 8, 1913.

His death certificate from 1925 identified him as Dr. John Charles Henry Müller, but the parents are correct so we know it's the right man.

He was buried at the church cemetery where his father once preached in Walhalla, and his grave can be viewed here.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

August 11, 2015: The bride of mystery

The lady at the center of this group is the focus of this week's genalogical mystery. It's more about a curious name change, one that can't be explained from available resources.

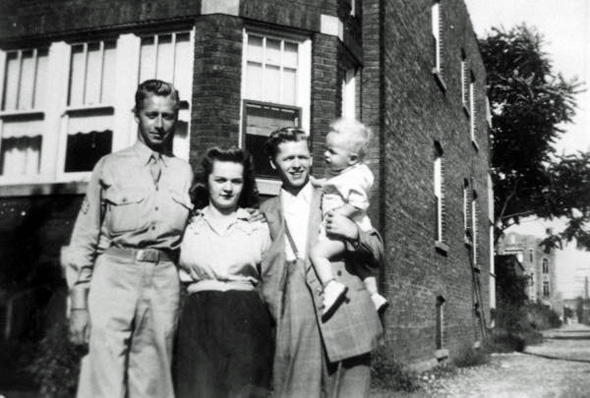

Brothers Tom and Al MacLaughlan, plus Al's son Bob, form a friendly family unit with Al's wife Doris. She was born Doris Vern Rohde, daughter of Frank Rohde and Marie or Mae Garrity in Chicago in 1925. Doris can be found in the 1930 U.S. federal census with her parents. No other children are listed so it appears that Doris was their only child.

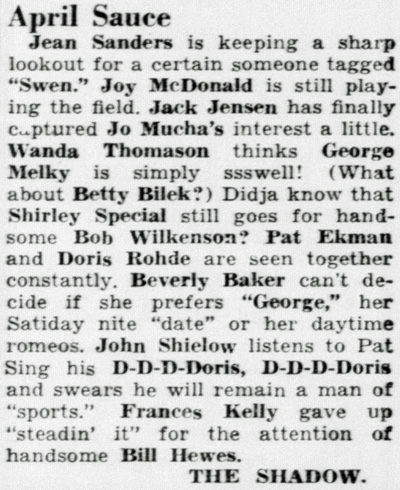

Doris and her family appear to be missing from the 1940 census, but the next mention we can find of her is in a suburban Chicago weekly newspaper, the Auburn Parker, pictured at left.

The pseudonymous author of this gossip column notes that in April 1941 Doris was keeping regular company with one Pat Ekman. The entire column was rather odd with a distinctly voyeuristic tone.

But things had changed just a few months later. The same home-town newspaper reported (below) on August 27, 1941 that Doris was engaged -- not to Mr. Ekman but rather to Al MacLaughlan Jr.

The odd thing about this: her surname had changed. In this clipping she's listed as Doris Vern Kaske with a different set of parents.

Searches for Mr. and Mrs. Kaske, using any number of spelling variants, bring up no useful documents, so we're left to assume that her father died or her parents divorced and the former Mae Garrity married a Charles Kaske, whose surname was taken by his stepdaughter.

Or perhaps the error was with the Auburn Parker newspaper, which, despite its devotion to local gossip, may have neglected the facts.

When the couple married a few months later in Kankakee County, Illinois, Doris was using her original birth surname, Rohde, again. The collection "Kankakee County, Illinois Marriage Index, 1889-1962" lists the marriage date as November 15, 1941.

It remains a curious footnote to a romance of the past.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

August 2, 2015: Happy home

My cousin's photograph collection, documenting our Petersen clan from the the 1870s and moving forward through time, often included random snapshots of houses. Sometimes the address was written on the back, sometimes not, leaving us to wonder whose residence was being captured, and for what purpose.

This house was in Omaha, Nebraska at 869 South 50th Street. We know that our ancestor Catherine Petersen Mikkelsen traveled from Chicago to visit her brothers Alfred and Peter about 1933, so a fair assumption is that this was one of their homes.

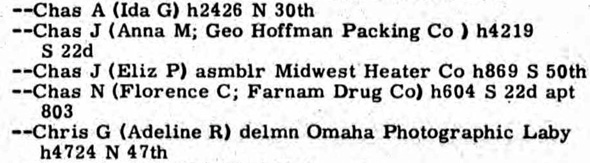

Close! It was actually the home of Alfred's daughter Elizabeth and her husband Charles J. Hoffmann, a mechanic in Omaha.

Charles and Lizzie had three boys (Charles, born in 1918, John, born in 1920, and Albert, born in 1922. But according to the Omaha city directories that family lived elsewhere for most of the period between 1920 and 1950. They moved house fairly often, for reasons unknown. But the 1954, 1955, and 1956 city directory shows Charles and Lizzie at that address.

In fact the boys appear to have moved out in their own by the time Charles and Lizzie relocated to 50th Street. But Lizzie and her Chicago cousin kept in touch throughout the decades, and a picture of the Hoffmann's new house (maybe it was the first they'd ever owned, or the one they liked best) ended up in the Catherine Petersen Mikkelsen collection.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

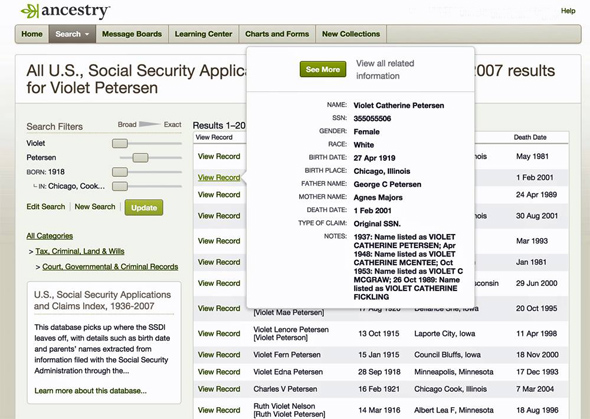

July 21, 2015: Violets are sweet

The new Ancestry.com database, "U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007," has a lot of useful information for those who applied for social security benefits or who may have made a claim for benefits.

My grandfather's niece, Violet Petersen, was "lost" for the reason that women are often difficult to trace: by changing her surname with marriage. I knew about her first marriage to James A. MacEntee in Chicago in 1940, but I figured that marriage must have ended, because I was getting no hits searching for Violet MacEntee.

Searching for Violet in this new databases brings up multiple name as one marriage ended and another began.

She married again about 1953 to someone named McGraw, then again in 1969 to someone called Fickling. The SSDI record also provides her verifiable birthdate, a fact that had been missing from my database.

Luckily Violet turns up in California divorce records and in California and Nevada marriages, so I'm able to focus more on the details of her life using this SSDI index as a platform.

In cases where the person's parents are unknown, this resource also provides that information, making it a useful tool to push back a little further into family history.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

July 14, 2015: Two little lambs

We have so little to go on in identifying these children that all we can say is: they're probably Petersens, or closely related to them.

The cabinet card came from the collection of Catherine Petersen in Chicago, so of course they're unmarked! Presumably Catherine recognized them without an inscription. We're not as fortunate as she was.

We actually know more about the photographer himself. Louis Gamer was born in Germany in February 1851, according to the U.S. federal census for 1900, and emigrated to the United States in 1858. His wife Frances had a more rare birthplace. The census states that she was born "At Sea." Her parents were from Scotland and emigrated in 1861 or 1862. Louis had a photography studio in Omaha in the 1890s on South Sixteenth Street, where this photo was produced.

The image is slightly out of focus, which suggests that it may be a copy of the original. It's even possible that these children never lived in America but were the offspring of Catherine's sister or brothers back in northern Schleswig-Holstein, where the family lived before a large number of them emigrated.

The dark-haired girl is dressed in finery that would point to the late 1880s or early 1890s as a date, although it could be earlier as well. The blond-haired boy, seated, wears a typical dress that could be used for either boy or girl babies at the time. The trick to knowing that this is a boy: his hair is parted on the side.

Facially the girl resembles Catherine (in her youth) as well as Catherine's daughter Margaret. Of all the children of all the Petersen family members, only one exhibits the older-girl-younger-boy constellation. Andrew Petersen and his wife Karen Marie Johansen lived in Illinois for a time and their first two children were born there: a girl, Alma, in 1889 and a boy, Walter Andreas, in 1892. If this cabinet card represents those two children, if must have been taken around 1893 when Walter was still a baby. This fits the time frame, but there's no proving the theory.

What's more puzzling: if these are Andrew's and Karen Marie's children, why was the photo produced in Omaha? Well, if it were a copy of an original, any photography studio would have been equipped to duplicate it. Andrew did return from Kenosha, Wisconsin (his final home) to Omaha sometime in the 1890s for a reunion with his brothers. Perhaps he brought the photo along at that time to share with his brothers. And somehow the card made its way into his sister's collection...where it remains as a speculative mystery.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

July 2, 2015: A marvel in marble

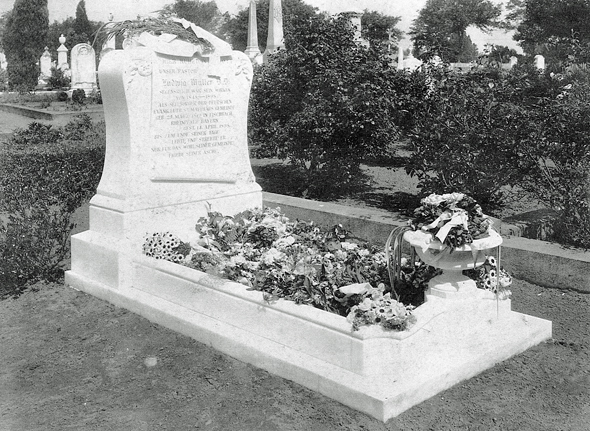

On the day of Ludwig "Louis" Müller's funeral in Charleston, South Carolina, it was clear from the picture above that his tributes were many. Just look at all those flowers!

If you click the image to enlarge it you can just about read the inscription on the marker, all in German, giving praise to the man who was the pastor of St. Matthew's German Lutheran Church in Charleston for fifty years. From 1848 until his death in April 1898 he was the symbol of his congregation and an inspiration to many.

It's unclear whether the marble is to blame or whether it was insufficiently treated to brave the elements for eternity, but the inscription is all but unreadable today. It has faded into softness and the letters' sharp angles are worn. This is one of the times we can be glad that a clearly professional photographer was on hand to record the wording.

Click here to read more about the accomplishments of the Rev. Müller and his family.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

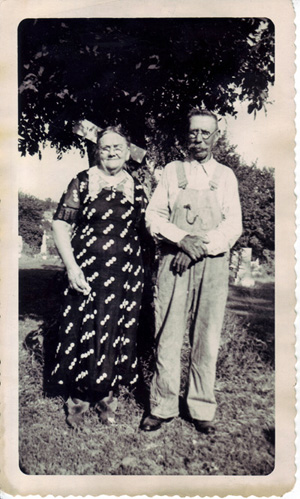

June 19, 2015: The whole picture

It looks like a simple snapshot, showing two older folks on a sunny day in Mason City, Nebraska. But that's just part of the story.

Unmarked (of course!), we nevertheless know that this is a photo of Catherine Petersen Mikkelsen and one of her brothers, Peter Hansen Petersen. Family resemblance to his brother Alfred makes it clear who's who. Alfred is seen here in this photo.

Note Alfred's snappy attire and the domestic setting in his garden, compared to another photo of Peter Hansen and wife Anna in front of their cornfield in Mason City.

But it's the background of each photo that has something to communicate. In the featured photo Catherine and Peter are posed at the edge of a cemetery. That wasn't a random decision.

Because we know that this trip took place in 1936-1937 (Catherine came from Chicago with her family for the visit) and we also know that Peter's wife Anna died in March 1936, my theory is that they were visiting her grave at the time of the photo.

It may have been unplanned, but it was an opportunity for the photographer -- likely Catherine's daughter Florence -- to emphasize, however slightly, the loss of Peter's wife.

The background of any photo may be random, but it's worth extra scrutiny in case its clues help to identify the time, place, or deeper meaning of its setting.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

June 10, 2015: Changing fashions, 1820s-style

Before photography existed — before the late 1830s, that is — capturing an image was the work of painters. And the cost of commissioning a portrait was out of reach for many middle-class folks in Europe at the time.

It's remarkable, then, that Johann Philipp Dressel could afford to have his daughter Anne Marie painted by a local artist. Mr. Dressel was a Metzgermeister, a master butcher, but not otherwise a rich man.

Perhaps the quality of the portrait indicates his financial limitations. It's not the most accomplished piece of work but it's pleasing and direct, probably accurately capturing much of Anne Marie's particular beauty and charm.

Dating this portrait depends mostly on her estimated age (she was born in 1810 in Reinheim, Hesse-Darmstadt) and her style of dress.

Compare Anne Marie with this portrait of Marie Caroline du Barry, she of the red feathered hat, painted in 1825. The bodice of their dresses is very much the same style with horizontal pleats gathered below the collarbone with a small jeweled brooch in the center of the low, dramatic neckline.

Both ladies also show evidence of a figure-hugging corseted waistline, a new fashion element beginning in the mid-1820s. This replaces the high empire waist and floating straight skirt popular in the previous decades.

We can see another similar dress style on Countess Amalie Maximilianovna Adlerberg, resplendent in her pearls and lofty hairstyle below, who was born in Paris but brought up in Darmstadt.

Here the horizontal pleats are gathered by a vertical strap sewn into the bodice, just like in Anne Marie's dress, and in place of a brooch there's an old-fashioned pink rose. The Countess also shows her tightly corseted waist with narrow vertical panels similar to the ones we can see on Anne Marie's waistline.

Both the high-born ladies have shorter sleeves than Anne Marie Dressel, but that's simply a style variation. And both the older ladies' portraits are clearly the work of a more accomplished artist. But Anne Marie's is pleasing enough, and quite a rare find when most family photographs can only reach back to the early 1840s...if you're lucky enough to own one.

By comparing these three paintings, two of which carry reliable dates, we can estimate that Anne Marie's portrait was painted about 1826-1827. That would make sense given her age at the time, 16 or 17 years old.

Was the painting a commemoration, perhaps of her engagement to up-and-coming haberdasher Ludwig Schuchmann? That's a distinct possibility.

They were married in November 1828 and had two children, Elise (1829) and Philipp (1830). About a decade later all relocated to Charleston, South Carolina.

Ludwig, known as Louis Schuckmann once he established his business there, was a respected purveyor of fine fabrics and decorative accoutrements. Anne Marie Schuckmann was a respected lady in Charleston society and became renown for her fine needlework.

Thanks to her descendants, who kept the portrait as a treasured legacy, we're fortunate to know what our ancestor Anne Marie looked like.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

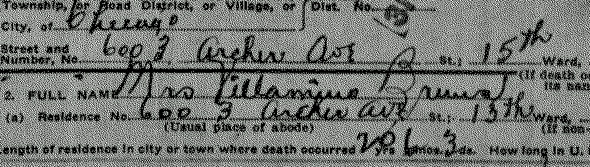

May 20, 2015: A death in the family

The reliability of index transcriptions is all over the map. Thus, when I came across a wildly improbable spelling in Ancestry.com's collection "Illinois, Deaths and Stillbirths Index, 1916-1947" for Elizabeth Bruns' death record (her first name is transcribed as "Villamino"), it took all my wits to figure out how they saw Villamino in Elizabeth. Could the handwriting be that bad?

Seventeen dollars is all it takes to order the actual death certificate from Cook County's Genealogy Online service, and sure enough, my great-grandmother's first name appears to be "Villamina." Everywhere else she was known as Elizabeth or Lizzie. What's the deal here?

Most of the other information on the full death certificate seem to check out. Her husband, the informant, was indeed B. A. Bruns (Bernard Augustus, known in the family as Gus). In the 1920 federal census the family lives at 6003 Archer in Chicago, and that's the place of death listed on this certificate.

The other information is approximately correct. Her father's and mother's names (as seen above in an 1855 baptism record for their twins Clemens and Gerardus) were John (not Gus!) Robers and Theresia Schulte. Elizabeth was born on June 29, 1860 (the death certificate says July 29, 1959...close enough for our purposes).

But where was Elizabeth or Lizzie ever known as Wilhelmine -- my take on the name the clerk was trying to spell?

Currently we don't have Elizabeth's baptism record from St. John the Baptist Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, where she was born, but I've put in a request to see whether they can find it. My theory is starting to develop. It was common for children of German immigrants as well as Germans themselves to discard their actual first name (Vorname) and used what we'd call the middle name and they called the Rufname or appellation name.

Perhaps that's the case with Elizabeth Robers Bruns. Gus Bruns, her husband, used a nickname for his every-day monicker that was derived from his middle name Augustus. It makes sense.

If so, it suggests that Elizabeth's actual first name was Wilhelmine, and widower Gus was following legal guidelines for reporting her true and accurate name, as best he could remember. If St. John the Baptist can come through with a baptism record for Lizzie, as they have for her older siblings, we may be able to prove it.

Fingers crossed!

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

May 7, 2015: Portrait of a lady

When you find an original cabinet card in the family vault, it can really help you reconnect with the past.

Karen Marie Johansen, born in Felster, Denmark, was probably nineteen in this photograph, which was taken in Chicago, Illinois shortly after her 1889 marriage to Andreas Petersen.

The marriage itself took place in York, Nebraska, where Karen Marie and her sister Anna Christina had emigrated in 1887. In fact, both Johansen girls married brothers. Andrew, as he was later known, had an older brother Peter Hansen Petersen, who had married Anna Christina in 1887.

Peter and Anna stayed in Nebraska where they farmed for the rest of their days. Andrew and Karen Marie lived for a time in Russell, Illinois north of Chicago before making a permanent home in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Andrew was a teamster, a driver of horses, and he and Karen Marie had six children.

This image shows the beginnings of the sleeve puffs on her dress that would give way to the more exaggerated leg-o-mutton sleeves some five years later. But in 1889-1890 this is a neat, tailored look, with woven wool trim and a nice brooch in the shape of a crescent at her throat. The other brooch may be a watch chain.

The Bell photography studio listed its address as 96 State Street, but perhaps they moved around the neighborhood. There was a Bell Art Company at 209 State Street in the early 1890s, found in a listing in Chicago Photographers, 1847 through 1900, published by the Chicago Historical Society.

Andrew died in 1918 but Karen Marie went on to a second marriage to a Christian W. Feldschau and travelled to the West Coast with him. He died in 1925 in Mt. Ranier, Washington. Twice a widow, Karen Marie Feldschau settled in Lake County, California to be near her grown children. She died there in 1949 at the venerable age of 79.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

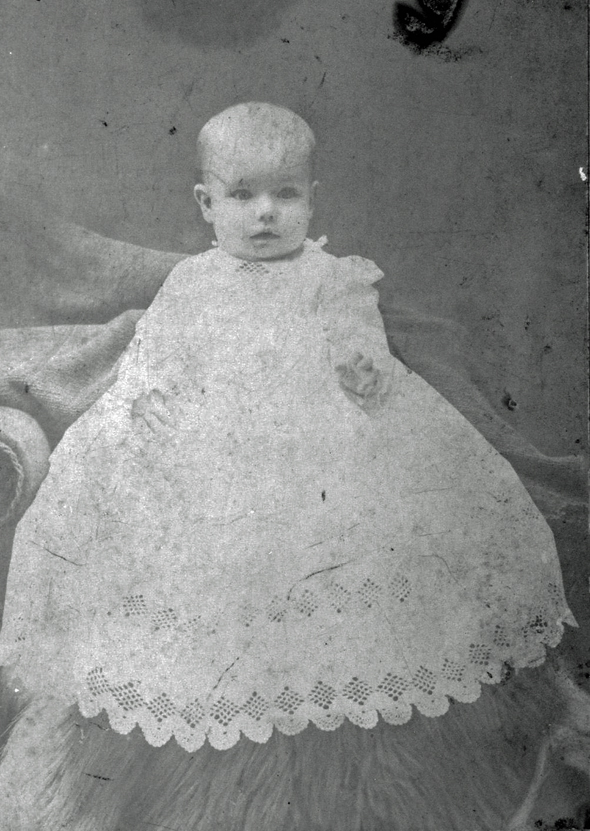

May 2, 2015: Baby's first portrait

In times like these, when babies who were just born today can be photographed when they're only a few hours old, it's easy to forget that most babies in the past weren't seen by the camera lens for weeks, if not months.

In the 1880s, photographing a newborn meant navigating to a local photography studio, and generally required that the baby be able to recline or sit up, assisted or not, and keep still while doing it. Daunting tasks!

Young George Henry Bruns, born March 26, 1887 in Cincinnati, Ohio, was probably about four to five months old in this portrait (click to see an enlargement). He's dressed in an elaborate gown of white linen and lace with decorative eyelets at the collar and hem. His parents, Bernard Augustus Bruns and Elizabeth Robers Bruns, probably used the gown for all their four children. This style was very popular for boys as well as girls all during that decade.

The background of the photo is worth noting. At your left you'll see the leather arm of a comfortable chair arranged perpendicularly to baby George, and there are two fabric-draped protrusions behind him. Do they look like...human arms?

There's a good possibility that the fabric-draped backdrop is actually Elizabeth Robers Bruns herself, covered with a patterned blanket and holding the baby upright. Think that's farfetched? Take a look at these photographs for similar arrangements.

It made sense. The mother could provide a soothing touch and whisper a calming word or two during the photographic sitting, which by the 1880s, when dry photo plates were the norm, required only a few seconds of stillness to accomplish. An older child could be trusted to follow directions, but for a baby a more elaborate scheme was required.

If you have any solo baby pictures from the 1880s or 1890s in your collection, haul them out and give them a closer inspection. Maybe you also have hidden parents in the background.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

April 26, 2015: A life well-lived

If you have a few folks who came from the former Duchy of Oldenburg, this site can be very helpful. A group of volunteers in Germany has been providing emigration information for people who left Oldenburg for the New World. One of these immigrants to Charleston was Sophie Friedericke Ulrichs (born Hinrichs about 1801), who was known in her later years as Johanna Ulrichs.

Her Von Oven grandchildren, all merchants, came to settle in Charleston in 1878 and apparently she accompanied them. Johanna appears in the 1880 federal census sharing their home.

The Oldenburgische Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V. website had Johanna's emigration year but had no information about her death year, which realistically must have occurred in Charleston.

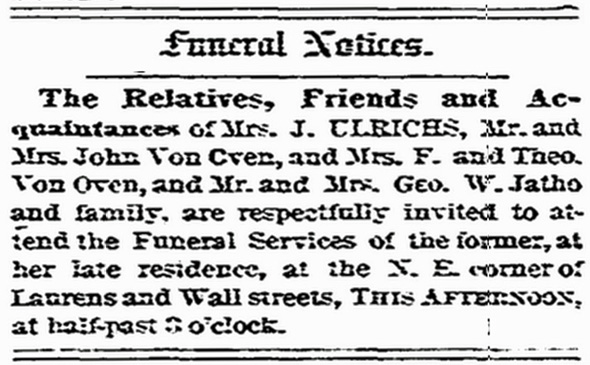

But the Charleston News and Courier for October 28, 1884 carried Johanna's funeral notice, and we notice some familiar surnames. The Von Oven men were her grandsons, all of whom managed successful grocery and wine shops in Charleston. Arnolda, her granddaughter, had married George W. Jatho, a successful merchant broker in Charleston.

It's uncertain where Johanna was buried. There were two cemeteries associated with the local German community. Her name doesn't appear in the list of burials for Bethany Cemetery, so it's likely that she was interred in Magnolia Cemetery, a more popular option for the Von Oven and Jatho families.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

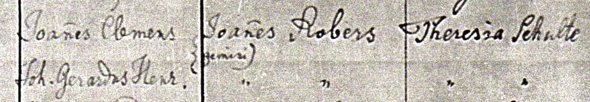

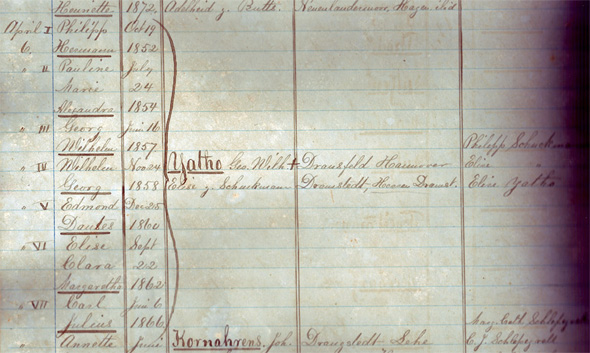

April 19, 2015: Baptism en masse

On April 6, 1873 and surprising number of Jatho children were baptized at St. Matthew's German Lutheran Church in Charleston, South Carolina. In fact, the entire family was involved, with their uncle Philip Schuckmann and grandmother Elise Schuckmann acting as godparents, along with their mother Elise Jatho. Click the image to enlarge.

Philip, the oldest, was by this time twenty-one years old. The youngest, Carl Julius, was seven.

There's a mystery about the family's religious affiliation during these years. A reasonably exhaustive

search for any church documents for this family turns up only one prior to this event:

a

one-line index to an 1853 marriage between Wilhelm Jatho, a watchmaker from Kassel, and his twenty-three year old

bride Elisabeth Schuckmann, born in Darmstadt. The marriage index is from Saint Johns Lutheran Church in Louisville,

Kentucky, a city where there is no known familial connection on the bridegroom's side, and an only speculative

one on the bride's (she may have had cousins there).

Until this 1873 record from St. Matthew's, the children's records aren't found in the city. They're not in the other local Lutheran church, St. John's, an even older German congregation in Charleston, nor in any of the non-Lutheran parishes in Charleston.

This is curious, because there are several news stories in the Charleston newspapers about the two elder children, Philip and Pauline, participating in St. Matthew's church picnics and even winning awards for archery or singing. Those stories appeared prior to this en masse baptism record.

Whatever the reason, we're lucky to have this record, penned in the fine hand of pastor Ludwig Müller who had led St. Matthew's since 1848, because it contains the full names and exact birthdates of all the children. Lacking their original baptisms, this entry is the next best thing. It's still a derivative record, based on secondary information, but it's still a valuable and usable citation for genealogical purposes.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

April 13, 2015: Seeing double

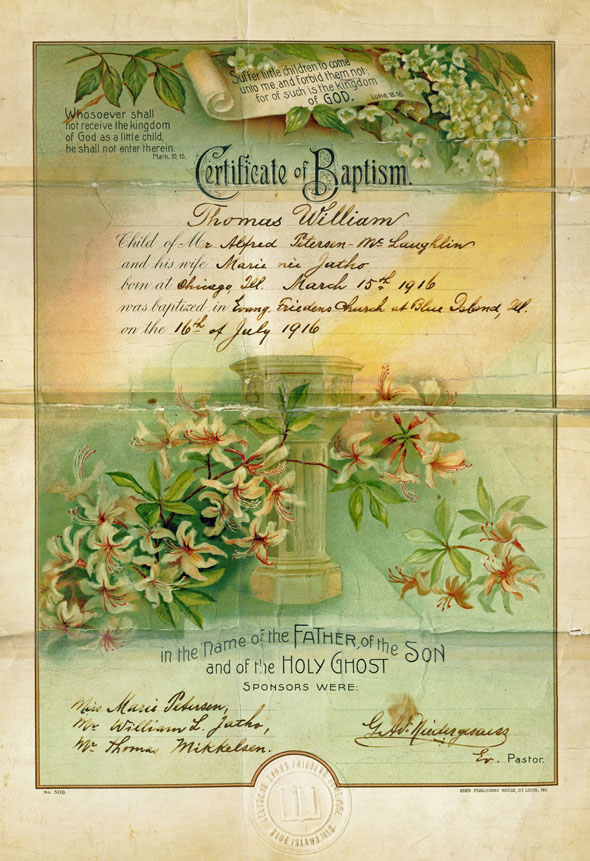

I know this document well. It served as a substitute for my father's birth certificate, which technically didn't exist. Cook County didn't require them until 1916, and even then some folks were inclined to ignore civil registration altogether long after it had become the norm.

Baptism certificates, especially fancy ones like this with its heavy embossed official registration stamp, were regarded as official documentation in the absence of any other. A person could even qualify for a U.S. passport with a baptism certificate like this in hand.

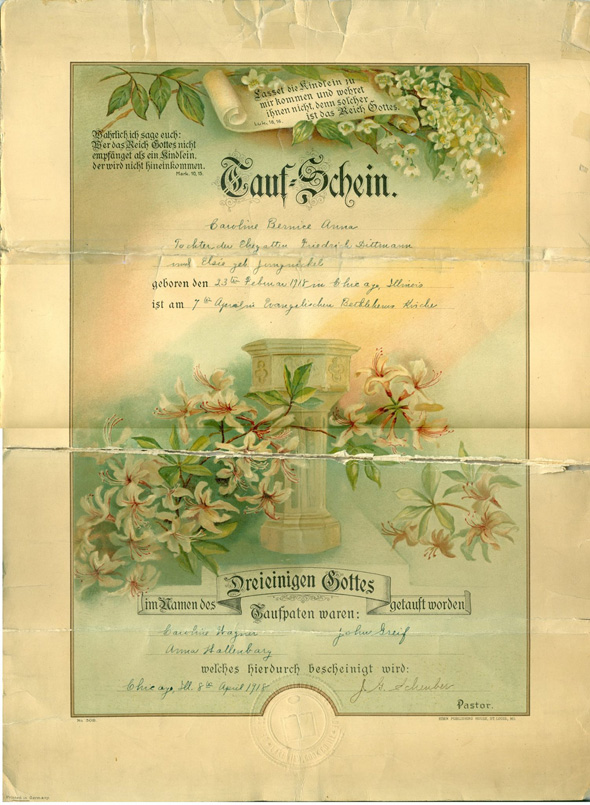

To my surprise, there was a German version too.

Both versions bore the same scriptural quotations and formats, just in different languages. They remind us how heavy a German presence there was in the Midwest during the early twentieth century, and how prevalent German as a language was found in various neighborhoods in the United States. Certainly the market for German-language documents was still strong up until the 1920s. It wasn't rare, for instance, to find county birth registries and certificates filled out by German-speaking doctors and midwives. A cursory search of the Cook County birth certificates from 1885-1920 will turn up several handfuls of such documents.

Long-form baptism documents such as these examples also demonstrate their usefulness in revealing the godparents of the child. As was typical, the chosen godparents were usually important to the family in some way, either as close family members or friends, but often leading to further revelations about the family dynamic.

The Eden Publishing House in St. Louis, Missouri was the source for these elaborate templates. The blank certificates were printed in Germany, then were shipped back to the United States, and likely sold popularly wherever an evangelical or Lutheran German congregation happened to exist.

The Eden buildings are still standing in St. Louis. Now part of the National Register of Historic Places, parts of the structures have been converted to trendy loft condominiums.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

April 7, 2015: Lady in waiting

Waiting to be identified, that is!

Around 1907 someone in the Mikkelsen household got a camera to use at home. Snapshots begin to show up around that time documenting everyday events at their Chicago home---Catherine Mikkelsen's new baby Florence, who was born in 1907; proud father Thomas Mikkelsen walking with toddler Florence a year later; Florence, now a young schoolgirl, posing with her half-brother Clarence Petersen in the front yard.

Catherine, as we've lamented before, wasn't always diligent about marking photos with names. If we're able to recognize some, all's well and good. But the one above, with an out-of-focus Catherine on the far left...well, who are the other ladies?

Another shot from the same day shows Catherine more sharply (with that impossibly small waist... one can only imagine the staying power of corsets at the time) standing with two older women. The younger woman all in black, with a not-yet-standing baby, is the central focus of the picture. Who was she?

Sometimes it takes years for all the clues to line up as neatly as pins. The woman is dressed all in black, and the outfit, apparently in black satin with lace trim, would be fashionable for the later part of the 1910s. She wears glasses, and that's important to note, because there weren't very many other spectacled relatives in Catherine's family. The baby wears the standard white dress that was popularly used for both girls and boys until they were old enough to walk. There's a hint of a side part in the baby's hair, which tells us this is likely to be a boy.

The mother's dress, and the older woman's black blouse and skirt, we can interpret as mourning clothes. The rules weren't as strict in the nineteen-teens as they had been in earlier decades, but some families, particularly those with old world customs, still observed them.

Then there's this photo, from some time a bit later.

This one was marked on the reverse and shows the studio setting for a wedding portrait of Martha Petersen, widow of Catherine Mikkelsen's son Peter H. Petersen, and Herbert Allen, a teamster. Martha is dressed in her best, from her cloche hat down to her sparkling patent-leather shoes, her bouquet at her side. Herbert, natty in his new suit and bow tie, stands proudly beside her.

The resemblance between the lady in black, holding the baby, and Martha Krohn Petersen Allen, is now striking, and I think it's safe to say that we can identify her in the earlier photos. The baby was Alvin Herman Arthur Petersen, born in July 1917, nine months after his father Peter Petersen died of nephritis in Chicago.

Who were the other older ladies in the photos? One of them may have been Martha's mother, Augusta Krohn---possibly the other lady in black. In the 1940 census Herbert and Martha Allen, along with Augusta Krohn, lived together with Martha's youngest sister in Milwaukee. Thus we know that Augusta was alive when her grandson was born, and she'd have been an expected member of the family group picture.

The other lady, with her hair piled high atop her head, appears in several snapshots taken in and around Catherine's home at 531 36th Place, where Catherine and Thomas Mikkelsen lived at the time. Another relative? A close neighborhood friend? That's still unknown and yet to be determined. She turns up in engagement and family photos regularly, so perhaps some clue will lead to her identity at some point in the future.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

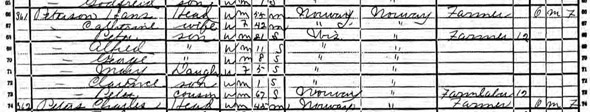

March 29, 2015: The mysterious Peter Petersen

First things first: none of these Petersens were from Norway. They were from Schleswig-Holstein, so if the enumerator had done his job (click the image to enlarge it), he would have written Germany as their country of origin.

Enumerators managed to mangle things often, but getting an entire nationality wrong wasn't that far out of the imagination. It depended whom you asked---a member of the family was the best resource, but even they might give wrong information on occasion. Or in this case it looks more as though the enumerator made the mistake himself. There was another Norwegian fellow below the Petersens and maybe the census fellow had Norwegians on the brain.

But this is clearly my great-grandparents and their children, who showed up in nearly the same arrangement in Chicago in the 1900 census. Here they're living on a farm they owned in Brookfield, Wisconsin, just outside of Milwaukee. The family is minus elder daughter Margaret, who died in 1903, but they've gained a cousin, Peter Petersen, born about 1838, presumably in northern Germany like the rest of the adult family.

So who's Peter?

The only person in the family who matches that birth year and who could possibly be described as a cousin---a term with a bit of fluidity in its definition at the time---was Enewald Petersen, who was actually an uncle to Hans and Catherine Petersen. State census records were often not as verbose as federal census records, so Wisconsin didn't record an emigration year. That would have been helpful in trying to determine who this fellow really is.

Enewald wasn't a popular name in the New World, and it's possible that this Peter Petersen attempted to pick something that sounded less foreign. Peter was also a very common nickname for anyone with the Petersen surname.

No trace of a likely candidate has turned up in any other records, either in earlier censuses, death records from Wisconsin, or subsequent censuses. Hans Petersen died this same year, just a couple months later. Catherine and her children moved back to Chicago. By 1910 Catherine was remarried to someone who was likely a family friend from the Old Country, Thomas Mikkelsen. Peter was nowhere to be found, but there's a chance (with luck!) that some evidence will be revealed someday.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

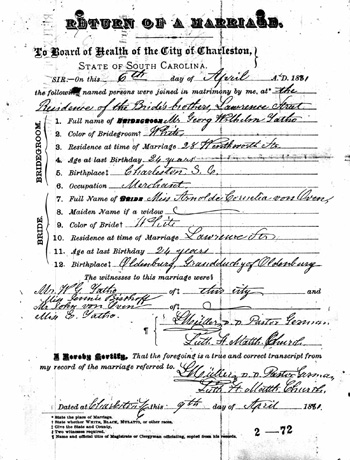

March 16, 2015: Marry once, marry twice

There are two prominent Lutheran churches in Charleston, South Carolina and my ancestor George Jatho was married in both of them...to the same lady!

Until the online collection "Charleston, South Carolina, Marriage Records, 1877-1887" became available via Ancestrylibrary.com, all I had was a scan of a registry entry for St. John's Lutheran Church marriage books, the original German-language congregation in Charleston. I assumed that this was all there was.

Now that the actual marriage record is available, I see that there was also a marriage under the auspices of St. Matthew's as well. Click the image to enlarge and read the details.

The bride was Arnolda Cornelia von Oven, who had emigrated from Oldenburg along with her brothers, who were all active merchants (grocery mostly) in the city.

She was marrying George William Jatho, the Charleston-born son and namesake of a German immigrant, Georg Wilhelm Jatho, who had been a jeweler and watchmaker in the city until his death in 1870. There were still plenty of Jathos in Charleston, and you can bet they and their cousins were all a part of the ceremony.

Both German congregations held services in German, but by 1881 St. John's had relaxed its language requirements and switched to the more common English service. Arnolda, new to English, may have felt some comfort in a service performed in her native tongue, for which the Rev. Ludwig Müller (who signed this document) was renown.

The verbose certificate gives the witnesses too: the bridegroom's brother and sister William G. Jatho and Elise Jatho, the bride's brother John von Oven, and a family cousin, Jennie Bischoff.

It never hurts to leave as many records as possible. Here's a double wedding with a very different meaning.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

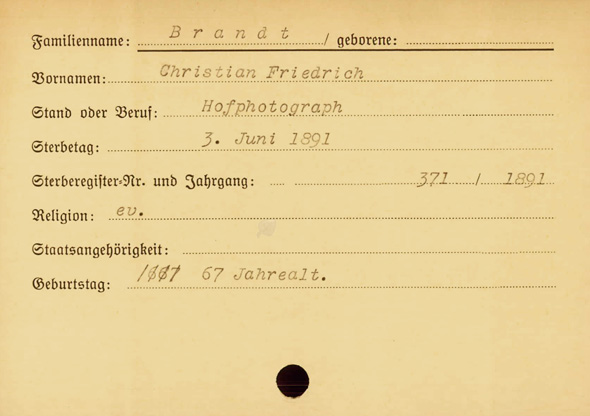

February 27, 2015: Photographer F. Brandt, Flensburg

Identifying the lady at left (click to enlarge) was not easy. For a long time she was completely unknown. The only available clue was the photographer and the location of his studio, and the datable time frame for the image itself.

In fact, we have more documented evidence for the photographer than we do for the lady.

First, the image itself: it's a small-format Card de Visite, cream card stock, original size about 1.75 by 2.5 inches. There's significant color damage from a fabric or cardboard matte of some sort that was used to encase it.

The lady's style of dress, with its prominent buttons, high collar, pleated cuffs, dark neck ribbon with some kind of floral brooch, help us date the photograph to 1869-1972. So too the hair, center parted with an elaborate braid crown, which could be a hairpiece or possibly the lady's own hair.1 The decorative carved chair and table are also representative of photo studio decor during this era, as is the size of the original image itself.2

The reverse of the Carte de Visite (click to enlarge) carries the stamp of F. Brandt, royal court photographer, winner of the Grand Golden King's Medal, and winner of photography competitions through Europe: "Preisgekrönt auf den Photograph Ausstellungen zu Berlin, Paris, etc."3

This photo of Margarethe "Magretta" Jensen Petersen was taken at the midpoint in the career of Christian Friedrich Brandt. He was born in 1823 in Schleswig to Christian Wilhelm Brandt, a bookbinder. Friedrich was trained in the craft by his father and was expected to join the business. After a sojourn throughout German territories to learn more about graphic art---and, one source believes, to work with Gregorius Renard in Kiel, then the most accomplished daguerreotypist in Schleswig-Holstein---Friedrich returned home.4

Friedrich Brandt collaborated with his father as a bookbinder from 1848 but by 1852 had opened his own photography workshop in Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein, and was known for his good-quality portraits. His reputation as a photographer was enhanced around 1863 beginning with a series of architectural and still life photographs. His innovative approach to photographing altarpieces was achieved by temporarily dismantling them to situate them outdoors where he could take advantage of direct sunlight and dark backdrops to highlight strong shadows and angles.

In 1864 Brandt achieved his greatest acclaim for a series of photographs taken during the final days of the Danish-German war, showing troops in situ on the battlefield. He was, in fact, one of only four photographers to be invited to do so.5. This commission resulted in an economically advantageous period, during which Brandt continued to explore photographing and documenting medieval sculpture.

From 1863 to 1883 Brandt worked chiefly as a portrait photographer in Flensburg, with at least five photography studios open throughout the town. Brandt closed his workshop in 1883 but suffered monetary reversals and was unable to work further. He and his wife survived in local alms-houses and Brandt died in 1891.6

Notes

1. Maureen E. Taylor, Uncovering Your Ancestry Through Family Photographs, second edition. Cincinnati: Family Tree Books, 2005, p. 89.

2. Gary Clark, "Carte de Visite," PhotoTree.com (website online: http://www.phototree.com/id_cdv.htm), 2013, accessed February 22, 2015.

3. F. Brandt, photograph of Margarethe "Magretta" Jensen Petersen, from the collection of Cathie Meyer, Chicago IL, digital image created in August 2005.

4. Klaus Oberländer, "Photospuren...Photographen + Ahnenforschung" [Photo tracks...Photographers and Genealogy], http://www.photospuren.de/ph_brandt.htm, accessed Febuary 21, 2015.

5. Rolf Sachsse, "Brandt, Christian Friedrich (1823-1891): in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, John Hannavy ed., New York: Routledge, 2007, p.201, accessed online via Google Books, short URL http://goo.gl/b58C3B, February 21, 2015.

6. Ancestrylibrary.com, Flensburg, Germany, Death Index Cards, 1874-1982 (database online), Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Karteikarten zu dem Personenstandregistern Tod, index cards, Stadtarchiv Flensburg, Flensburg, Deutschland. Accessed February 23, 2015.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

February 9, 2015: Mikkelsens in Flensburg

Thomas Mikkelsen and his first wife Helene Sievertsen were both living in Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein when their second daughter was born in 1878. Records from Flensburg are not easy to obtain and are generally available only to local researchers who have access to the archives.

But here's a bit of luck, although the message is a sad one. Ancestry.com has been adding cards from an index of records from the region. From 1874 in Prussian provinces, such as Schleswig-Holstein, a civil registry was set up to record information kept up until that time by ecclesiastical repositories. The database "Flensburg, Germany, Death Index Cards, 1874-1982" is now available online, as are birth and marriage records too.

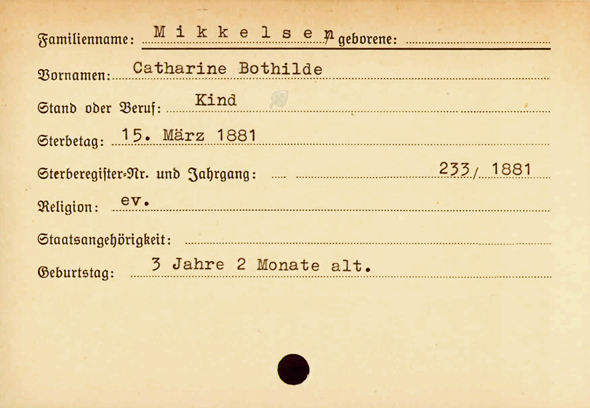

We can tell now that Catharine Bothilde, born January 19, 1878, died at the young age of three years, two months, and this is new information, not previously available. I'd suspected a death because the name was repeated for a third daughter born in 1884, one who lived to adulthood after emigrating as a child to the United States. Both girls were named for their maternal grandmother, Anna Cathrine Bothilde Petersen.

Although the record doesn't give the child's parents' names (an odd omission if the record was meant to be helpful to anyone), the age of the child corresponds almost exactly to Catharine Bothilde's birthdate. So I'm pretty confident that we can accept this record as proof of the first Catharine's short life.

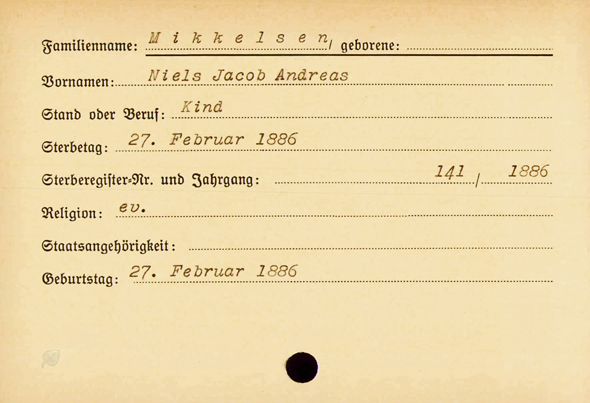

I'm more reluctant to make the same claim with this second record. Thomas and Helene did have a son called Niels Jacob Andreas who appears not to have made the trek across the pond to America, so the assumption is that he died too. But the birth date recorded here isn't correct for the Niels whose baptism record was previously supplied by a local researcher.

Our Neils was born February 21, 1880 while the family was still living in Ladelund, about twenty kilometers west of Flensburg. This record appears to indicate a child who lived only one day, February 27, 1886, and who died in Flensburg. Although the name matches our Neils, without the name of the parents there's no way to verify that he's from the same family.

I noted that these indexes are actually transcriptions of the original records, which were likely not typed neatly on modern index cards but were more likely handwritten in quill pen and ink. It's possible that the transcriber made an error (and it's tempting to imagine a misreading of 1886 for 1880 in whatever handwritten record the typist was transcribing). But at best this scenario is unlikely.

Although we don't know what happened to Niels Jacob Andreas Mikkelsen, there's no mention of him in the family's emigration records, no surviving photos in the family's collection. My assumption is that he too died young, but we're left with a mystery as to where, when, or why.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

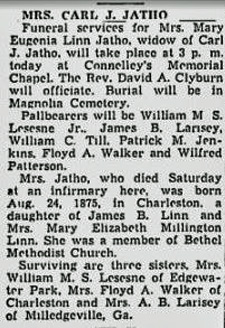

January 30, 2015: Lamenting the late Mrs. Jatho

It was accurate, I suppose, for the 1954 Charleston News & Courier to describe Mrs. Jatho as the widow of Carl J. Jatho. Legally she probably was, although they hadn't lived together as man and wife since 1910 or so...and in any case C.J. had died himself in 1929 in Bartow County, Florida, where he'd married again and raised a family.

Of course it's very likely that C.J. had never divorced Mary Eugenia Linn Jatho. South Carolina was the only state in the Union to ban divorce outright, for any reason, prior to 1950. Most states made it difficult to seek a divorce. In nearby Kentucky it required that the state legislature be convened to rule on any divorce proceedings. But in Charleston, where Mary and C.J. had lived, there was no way out...except to disappear.

With C.J. ensconced out of state with his new family, Mary Jatho continued to live inconspicuously in Charleston. She was not the first "grass widow" (a polite term for the situation) in the Jatho family. C.J.'s elder brother Edmund had similarly left his own wife, Edith Ripley Jatho, in New Orleans, where it was also difficult, not to say expensive, to end a marriage. In Edmund's case it appears that financial reversals (plus a little bit of larceny) compelled Edmund to leave town, where Edith had already attracted the attention of Robert Macmurdo, whom she married in 1895.

In Mary Jatho's case there was no remarriage. She made her living as a clerk and spent her later years in a retirement home in Charleston. This obituary mentions no surviving Jathos, although there were still a few in town, only her sisters and sisters' husbands. It was a quiet end to a life lived discreetly.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

January 20, 2015: Research your German ancestors online...soon!

I was pleased to see a major effort on the part of Germany's civil and religious archives to launch a new site. Archion is doing what the Danish archives began doing a decade ago: digitizing and uploading archived record books to the Internet.

It's a massive undertaking due to the fragmentary nature of German records. Prior to the unification of Germany in 1871 records were kept locally in archives that were reachable only by researchers who were familiar with them.

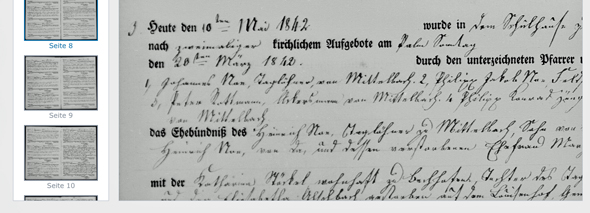

Here's a look inside the viewer, where you'll be able to select individual pages from a list at left, enlarge, and scroll from page to page.

Indications are that Archion will be a fee-based service after it launches at the end of March, but you can explore it now to see what categories of records will eventually be available online. Few actual records are online so far (they're highlighted in green) but there's great potential here to fill in gaps in regions where the cost of obtaining local records is prohibitive.

Yes, the site's in German for now, but an English language option is planned, probably in time for its official launch. Or you could just brush up on your German and dive right in.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

Write A Comment

January 3, 2015: Images from the past

Back in August I wrote about a cousin from Germany -- previously unknown to us -- who had discovered that our families share a surname. Our two lines branched off in the early 1770s and because none of our male Vonderschmitts every made it to the New World (we think, based on the evidence), we've never seen a photo of them.

Our new cousin was kind enough to share this image of his ancestor Georg Vonderschmitt, who was born in the 1880s in Germany.

Handsome fellow, too! Georg is shown about 1900 dressed stylishly with an elaborate cravat and pearl-tipped collar pin, with the high collar so common in the first decade of the twentieth century.

For genealogists the web can be a productive endeavor. Using the power of online tools like search engines, you can selectively post information about your family surnames in the hopes that search engines will index them. Once that happens, be ready for some surprise meet-ups.

We're very grateful to our cousin for reaching out. That's one of the true delights of genealogy. Only connect, as E.M. Forster wrote. What follows may just be a bounty of family history.

Show comments/Hide commentsComments

-

No comments yet.

No comments yet.